Negative Interest Rates Explained: Why Central Banks Went There—and What It Broke in Global Markets

Negative interest rates were never meant to be a normal feature of global finance. They were an emergency extension of monetary policy, used when conventional rate cuts and quantitative easing had already been pushed to the limit. For more than a decade, investors watched central banks flip the basic intuition of fixed income on its head: you paid governments and some corporates for the privilege of lending to them. At the peak in late 2020, roughly 18 trillion dollars of bonds traded with negative yields, close to 27 percent of global investment grade debt.

The keyword question, especially now that most negative policy rates have been unwound, is not just “what are negative interest rates” but “what did that experiment actually do to markets, banks, and investor behaviour”. The European Central Bank pushed its deposit facility below zero in 2014 and kept it negative until mid 2022, while Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark, and eventually Japan followed with their own versions of Negative Interest Rate Policy, or NIRP. Japan only ended its negative policy rate in March 2024, capping eight years of sub zero settings.

On paper, the logic seemed straightforward. If you make it painful for banks to park reserves at the central bank, they should lend more. If safe yields move deeply below zero, investors should walk up the risk curve toward credit, equities, and real assets. If currencies weaken under ultra easy policy, export sectors should gain traction. That was the theory. The practice was far more complicated and much more revealing about how modern markets respond to extreme policy regimes.

For investors, the episode matters for two reasons. First, it showed that the old “zero lower bound” was not a hard floor, but it still had practical limits once bank profitability and financial stability came into view. Second, it left a legacy. Even though policy rates are back above zero in Europe and Japan, real rates in some markets remain negative, and the scars from years of suppressed yields still shape behavior in credit, housing, and institutional portfolios.

So what exactly were central banks trying to fix with Negative Interest Rates, what did they actually achieve, and what did they break along the way.

Negative Interest Rates as a Policy Tool: What Central Banks Were Trying to Fix

When the ECB moved its deposit facility to minus 0.10 percent in June 2014, it was reacting to a stubborn mix of weak growth and very low inflation in the euro area. Traditional rate cuts had already pushed policy close to zero. Large scale asset purchases were under way. NIRP was presented as the next logical step within a broader easing package. The message was clear. Central banks would not tolerate a drift into entrenched deflation.

The operational objective was narrow. By charging banks on excess reserves, the ECB and later other central banks tried to pull down the entire short end of the curve, keeping money market rates close to the policy rate and reinforcing forward guidance. For the ECB, the deposit rate eventually went as low as minus 0.50 percent, and this setting stayed in place until mid 2022, when surging inflation forced a fast pivot higher.

Japan’s motivation for Negative Interest Rates had a different history but similar intent. After years of quantitative and qualitative easing, the Bank of Japan introduced a policy rate of minus 0.1 percent in 2016 as part of its attempt to break a decades long deflationary mindset. The idea was to reinforce a broader easing framework that also included yield curve control and heavy purchases of government bonds and ETFs.

Underneath the inflation story sat a financial repression story. Governments in advanced economies faced very high debt loads in the aftermath of the global financial crisis and the euro area crisis. Negative policy rates and aggressive QE compressed sovereign yields, making it cheaper to roll large stocks of public debt. In 2020 alone, more than 20 percent of newly issued sovereign bonds globally carried negative yields, which meant investors were accepting a guaranteed loss in nominal terms in exchange for safety and liquidity.

Central banks framed this as a temporary, targeted response to exceptional conditions. Yet once negative rates became embedded, the marginal benefit of going further down quickly came into question. Research from the IMF and others highlighted a tipping point where deeper negative settings start to compress bank profitability enough to weaken the transmission channel they were meant to strengthen.

In practice, most central banks kept their negative policy rates relatively close to zero, typically within a band between minus 0.75 and minus 0.10 percent. They also introduced tiering systems that shielded some bank reserves from the full charge, acknowledging that the lower bound was no longer purely a technical constraint but a political and financial stability boundary as well.

Global Markets Under Negative Interest Rates: Bonds, Currencies, and Asset Inflation

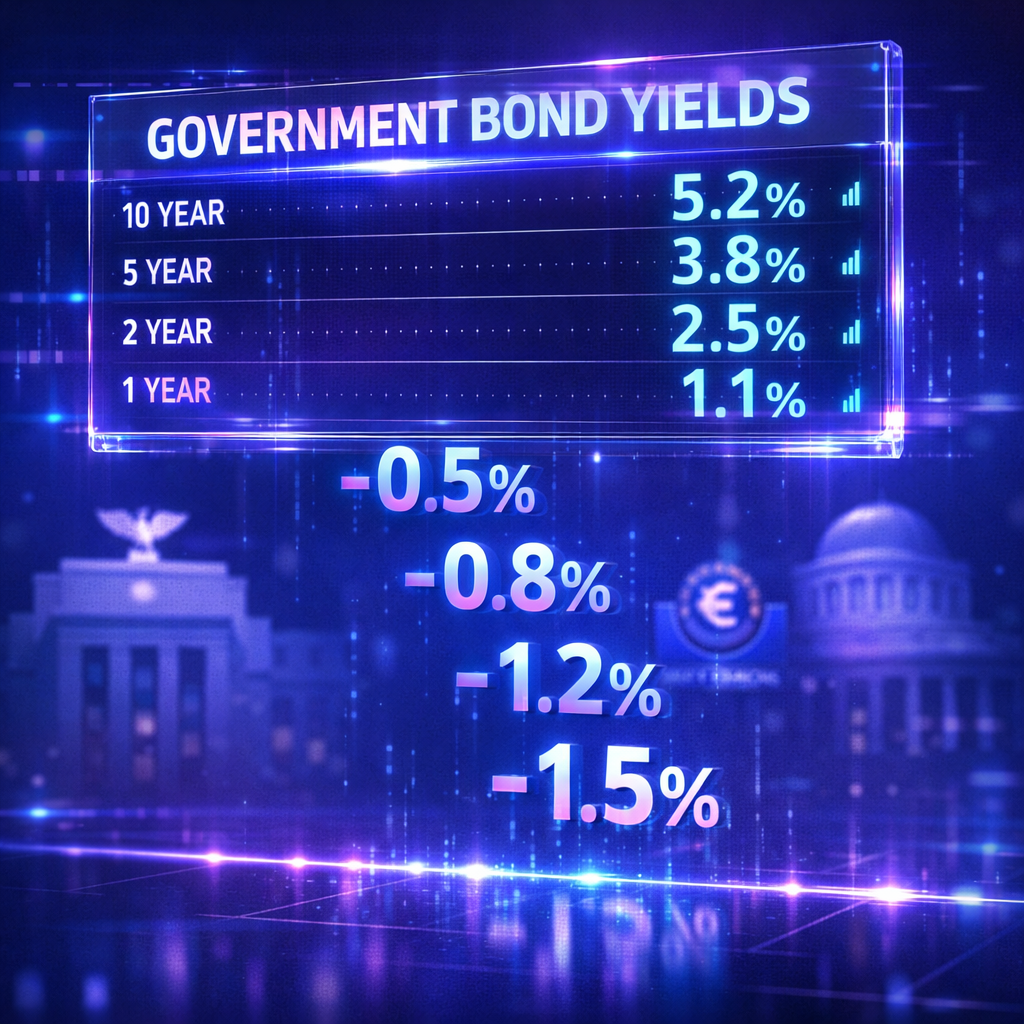

If you want to see the most dramatic footprint of Negative Interest Rates, you do not start with bank earnings. You look at the bond market. By December 2020, the face value of negative yielding debt had climbed to around 18 trillion dollars worldwide, including a large share of euro area and Japanese sovereigns as well as high grade corporates. The traditional anchor that “bonds always pay at least some nominal interest” was replaced by a new reality. Safety and regulatory treatment mattered more than positive carry.

For global allocators, this changed the opportunity set. Insurance companies and pension funds bound by solvency rules had to keep buying duration even at negative yields, simply to match liabilities. At the same time, investors with more flexibility moved into credit, emerging markets, private debt, and alternatives in search of positive real returns. That rotation compressed spreads and inflated valuations across risk assets. It also raised the question of how much of the rally was driven by fundamentals and how much by forced yield hunting.

Currencies felt the impact in a more uneven way. Negative rates were often sold politically as a way to weaken an overvalued currency and support exports. In practice, the signal effect of NIRP sometimes mattered more than the arithmetic. The ECB’s move below zero initially pushed the euro down against the dollar, and the Bank of Japan’s decision helped weaken the yen. Over time, though, relative growth expectations, terms of trade shifts, and risk sentiment often overshadowed the rate differential alone.

One of the more subtle distortions appeared in term premia. With central banks anchoring short rates below zero and hoovering up long duration through asset purchases, the compensation for holding long term bonds collapsed. For a period, some euro area sovereign curves traded almost entirely below zero out to ten years. That flattened term structure changed how investors priced recession risk, inflation expectations, and term liquidity.

Equities and real estate absorbed the spillover. When the discount rate in traditional valuation models falls toward zero, almost any long duration cash flow looks attractive. Price to earnings multiples expanded, and equity risk premia narrowed even before earnings had fully recovered in some sectors. In housing markets, cheap financing combined with pandemic era demand shifts to push prices to levels that later came under serious pressure during the rate hiking cycle of 2022 and 2023.

By early 2023, the mechanical presence of negative yields had faded. The last remaining negative yielding government bonds disappeared as global inflation forced central banks to lift policy rates back into positive territory and end large scale purchases. But investors are still living with portfolios that were built in a period when safe assets were priced as guaranteed small losses rather than as income sources. That experience changed risk tolerance and allocation habits in ways that will not vanish quickly.

Banks, Savers, and Pensions Under Negative Interest Rates

From the start, the most contentious debate around Negative Interest Rates focused on banks. Traditional banking relies on a positive spread between what banks pay on deposits and what they earn on loans and securities. When policy rates go below zero, it becomes very difficult to pass negative rates on to retail depositors, both for reputational and political reasons. That squeezes net interest margins and, over time, can erode capital generation.

Empirical work from the ECB, IMF, and various academic studies paints a nuanced picture. In the early years of NIRP, banks were often able to offset margin compression through lower funding costs, capital gains on securities portfolios, and credit quality improvements in a low rate environment. Over longer horizons, especially as policy rates went deeper and stayed negative for years, the pressure on profitability became more visible, particularly for deposit heavy retail banks with limited fee income.

That pressure had second order consequences. If bank ROE falls structurally, management has three options. Cut costs, raise fees, or reach for yield. In Europe and Japan, all three showed up. Cost cutting meant branch closures and headcount reductions. Fee increases hit households and small businesses via account charges and other services. The reach for yield dimension is the one that worried regulators. Studies found evidence that some banks responded to NIRP by increasing exposure to higher yielding, higher risk assets, which can undermine financial stability if the cycle turns sharply.

For savers, the optics were even more direct. Depositors in some countries began facing explicit negative rates on large balances, particularly corporate treasuries and wealthy households. In the euro area, several banks announced charges on deposits above certain thresholds once the ECB deposit rate had been negative for a sustained period. While widespread retail “cash in the mattress” behavior never fully materialised, the political reaction against perceived punishment of savers became a recurring theme in domestic debates.

Pension funds and life insurers faced a quieter but deeper challenge. These institutions promise long term, often nominally defined benefits. Their asset side now had to deliver those promises in a world where the safest bonds yielded zero or less in nominal terms. That created a powerful incentive to move into illiquid credit, infrastructure, and private markets. On one level, this shift supported productive investment. On another, it increased exposure to assets that are harder to value and exit in stress, raising questions about how these balance sheets would behave under a severe shock.

Central banks tried to mitigate some of these side effects. Tiered reserve systems reduced the share of reserves facing the full negative rate. Macroprudential tools were strengthened to monitor risk taking in banks and non bank financial institutions. But the basic trade off remained. The deeper and longer Negative Interest Rates persisted, the more the transmission channel shifted from “cheaper credit” toward “pressure on financial business models”. That is a very different environment than a standard rate cut cycle.

After Negative Interest Rates: What the Experiment Broke and What It Taught Investors

By 2022 and 2023, the story flipped. Inflation surged on the back of pandemic supply shocks, energy price spikes, and very loose financial conditions. The ECB lifted its deposit rate from minus 0.50 percent back to zero in July 2022 and quickly into positive territory. The Bank of Japan, always more cautious, finally moved its policy rate out of negative territory in March 2024 and began to dismantle yield curve control. By early 2025, commentators were already describing negative rates as “history”, at least in advanced economies.

The exit itself exposed what years of suppressed yields had built under the surface. Banks and insurers that had loaded up on long duration bonds during the NIRP era suddenly faced mark to market losses as yields repriced higher. Some institutions had enough capital and hedging to absorb the shock. Others discovered that apparently safe holdings could trigger liquidity stress when collateral haircuts moved and depositors grew nervous. Although the most famous cases, such as US regional bank failures, came out of a low but not negative rate regime, the underlying mechanism was similar. Long duration bought for yield in a very low rate environment turned into a vulnerability once policy normalised.

The broader market adjustment was just as telling. Sectors that had benefited most from ultra low discount rates, such as long duration growth equities and certain pockets of real estate, saw abrupt valuation resets. Investors who had moved into complex credit structures or private markets as a substitute for yield discovered that liquidity terms did not always match their need to rebalance. For allocators who built portfolios during the Negative Interest Rates period, the unwind became a real time test of how well they had priced duration, liquidity, and solvency risk.

From a policy perspective, the experience delivered mixed grades. On the supportive side, research suggests that NIRP did help ease financial conditions and raise inflation expectations, especially in the early years, by pushing down short and medium term yields and weakening exchange rates. On the cost side, it clearly compressed bank margins, nudged investors into riskier assets, and contributed to asset valuations that later had to reset painfully as inflation returned.

For central banks, one practical lesson is that the lower bound is not mechanical. Cash hoarding and cash logistics never became the dominant constraint. The real constraint turned out to be the resilience of the financial system under a prolonged regime of squeezed spreads and distorted term premia. Once profitability, risk taking, and political tolerance start to move the wrong way, pushing policy rates deeper into negative territory becomes counterproductive.

For investors, the lesson is sharper. Negative Interest Rates are not just another branch on the Monte Carlo tree. They fundamentally change the meaning of “safe assets”, the behaviour of intermediaries, and the shape of the efficient frontier. When yields on high grade bonds are pinned below zero, risk free income disappears as a portfolio anchor. The moment the regime ends, duration can become the main source of loss rather than protection.

So if the next downturn tempts central banks to flirt with negative policy rates again, what should investors remember. First, treat NIRP as a temporary distortion, not as a permanent reset of what fixed income is worth. Second, recognise that bank and insurer behaviour under negative rates can either amplify or mute the intended policy impulse, depending on capital strength and regulation. Third, price liquidity more carefully. The path out of negative rates often matters as much as the path in.

The era of Negative Interest Rates may be over for now, yet its legacy is still working through balance sheets and investment committees. It reminded policymakers that unconventional tools come with complex side effects. It reminded investors that yield is never free. And it left everyone with a more sober understanding of how far you can bend the structure of modern markets before something starts to crack.