What Is Vertical Integration? How Smart Companies Use Supply Chain Control to Build Moats, Margins, and Market Power

In theory, vertical integration sounds like a relic from industrial capitalism. Own your suppliers. Control your distribution. Manage the full value chain from raw materials to end customer. But in modern strategy, the question is no longer whether vertical integration is efficient. It is whether it is defensible. In an economy defined by platform wars, logistics bottlenecks, and razor-thin margins, owning more of the stack is less about control for control’s sake—and more about shaping your margin structure, delivery speed, data advantage, and pricing power.

This article unpacks what vertical integration really means today. It goes beyond upstream and downstream textbook definitions to look at how companies like Amazon, Tesla, and Apple use it as a strategic weapon. We’ll also explore where vertical integration breaks down, and why not every company should try to own everything in sight. Whether you are on the buy side assessing a portfolio company or on the operating side debating where to insource, understanding vertical integration is about more than operations. It is about leverage, risk exposure, and long-term optionality.

What Is Vertical Integration? Revisiting the Classic Concept Through a Modern Lens

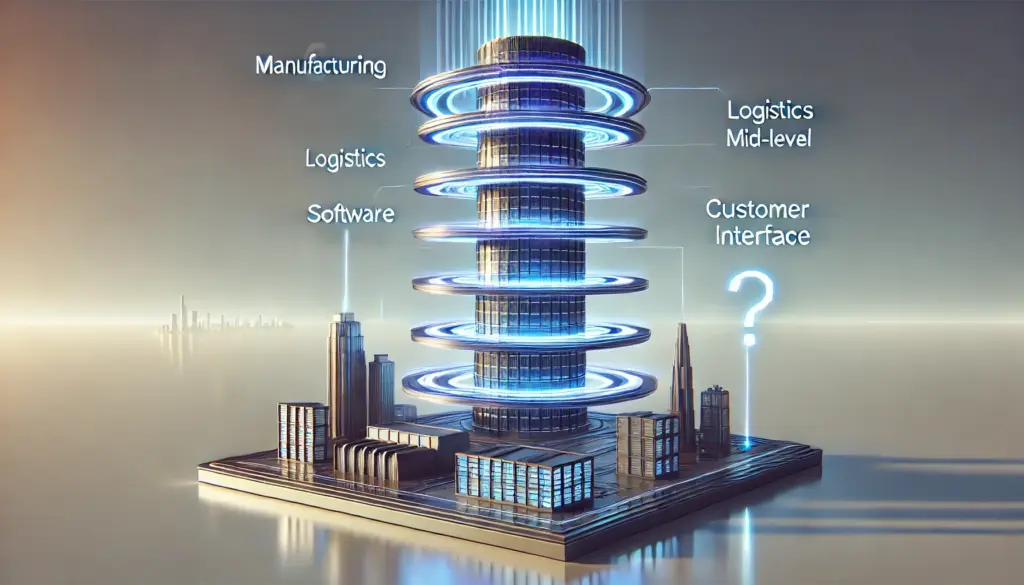

At its core, vertical integration means owning multiple stages of a company’s supply chain. That could mean backward integration, like a furniture company acquiring a wood supplier. Or forward integration, like a manufacturer opening its own retail stores. The goal in both cases is to reduce dependency, improve coordination, and capture more margin within the value chain.

But today, vertical integration is less about simple logistics and more about strategic control. In fast-moving, tech-enabled markets, the definition has expanded to include data ownership, software stack alignment, and direct customer relationships. This is not just about moving goods more efficiently. It is about shaping the full customer experience, capturing unique insights, and removing friction that competitors still suffer from.

Take the example of a modern consumer brand. Vertical integration for them might mean owning the Shopify backend, running their own fulfillment center, and managing customer service in-house. These layers create a feedback loop where the company controls every customer touchpoint. The outcome is not just faster delivery. It is better retention, more upsell data, and higher LTV.

For B2B SaaS companies, the idea plays out differently. A software platform might acquire an infrastructure layer like a payments processor or identity verification tool. This move not only improves margins but also hardens the moat. The company becomes less reliant on third-party APIs, more customizable for enterprise clients, and harder to replicate.

Even in traditional sectors like energy and agriculture, vertical integration has taken on new forms. Renewable energy firms increasingly develop, finance, and operate their own projects rather than outsourcing pieces. Food delivery companies build their own dark kitchens. In every case, integration is not just about cost—it is about alignment, speed, and leverage.

Strategic Benefits of Vertical Integration: Margins, Moats, and Competitive Leverage

So why pursue vertical integration at all? The obvious answer is margin control. By eliminating third-party markups, companies can improve gross margins and protect against pricing volatility. But in high-performing businesses, margin improvement is just the first layer.

More important is the strategic control it provides. Owning upstream or downstream functions means fewer coordination failures. It reduces the risk of supply shocks, misaligned incentives, or customer experience failures caused by third parties. This was especially clear during the global supply chain disruptions of 2020–2022, when vertically integrated firms like Tesla and Apple outperformed rivals in product availability and pricing discipline.

Vertical integration also helps protect proprietary data. When a business owns its entire workflow—from production to customer interface—it captures richer insight into user behavior, unit economics, and demand forecasting. That allows for tighter iteration cycles, better pricing decisions, and product development grounded in real usage data. In contrast, outsourced chains often mean handing valuable information to logistics partners, third-party sellers, or white-label platforms.

Another advantage is brand consistency. For companies competing on customer experience, owning the entire journey matters. It ensures service quality, packaging, support response, and delivery timing all reinforce the same value proposition. This is one reason why DTC brands like Warby Parker and Glossier invest heavily in their own retail footprints despite the higher fixed costs.

For acquirers or investors, vertical integration can also serve as a value creation lever. If a company has grown by outsourcing key functions, a buyer might see integration as a post-deal upside opportunity. That could mean buying a supplier to lock in pricing or investing in distribution to improve margin capture.

Of course, these benefits are not guaranteed. They depend on the company’s ability to manage complexity, build internal capabilities, and maintain focus while expanding its footprint. But when executed with discipline, vertical integration offers a powerful blend of operational leverage and strategic defensibility.

Vertical Integration in Practice: Real-World Examples from Amazon, Tesla, and Beyond

If vertical integration sounds theoretical, just look at how today’s most influential companies are using it to rewrite their industries. For Amazon, vertical integration began with logistics. What started as reliance on third-party carriers has become one of the most powerful private delivery networks in the world. Amazon now owns everything from fulfillment centers to aircraft to last-mile vans. This control gives it pricing leverage, delivery speed, and data feedback loops competitors struggle to match.

Tesla took vertical integration even further. Rather than relying on automotive supply chains, it chose to build everything from proprietary software stacks to battery factories. Tesla’s Gigafactories and in-house AI chips give it faster iteration cycles, better cost control, and deeper integration between hardware and software. When global chip shortages slowed down rivals, Tesla rewrote its firmware in-house and kept production moving.

Apple is another example of deliberate, disciplined integration. The company designs its own chips (Apple Silicon), controls its software ecosystem, and operates a tightly managed retail network. This allows for product experiences that feel cohesive, secure, and high-performing. It also gives Apple unmatched pricing power. By owning more of the value chain, Apple does not just cut costs. It commands a premium.

But not all examples are tech-driven. In the consumer space, brands like Warby Parker, Everlane, and Glossier have invested in their own manufacturing, distribution, and storefronts. These moves are about more than aesthetics. They let the brand control margins, manage inventory cycles more tightly, and deliver a uniform experience across all customer touchpoints.

In food and logistics, players like Sweetgreen and Domino’s have also embraced integration. Sweetgreen opened its own food prep facilities to improve consistency and unit economics. Domino’s owns its own delivery infrastructure, including order tracking software and driver networks, which allowed it to grow efficiently without relying on third-party apps.

Even in private equity, vertical integration shows up as a post-acquisition play. A PE firm buying a fragmented manufacturing platform might roll up suppliers or build proprietary logistics to capture more value. Integration becomes not just operational—it becomes a thesis for driving EBITDA expansion and exit readiness.

These examples share one thing in common: integration is never done just for scale. It is executed to shape strategy, deepen customer control, and harden the moat.

Risks and Tradeoffs: When Vertical Integration Becomes a Strategic Burden

For all its potential, vertical integration comes with serious tradeoffs. The most obvious is cost. Building in-house capabilities—whether in logistics, manufacturing, or software—requires significant capital and management bandwidth. What looks like a margin play can quickly turn into a distraction if not executed with discipline.

There’s also the issue of strategic overreach. Some companies integrate without a clear rationale, chasing control instead of alignment. This often leads to bloated cost structures and internal teams managing parts of the business they don’t understand. Integration only works when each layer adds differentiated value—not when it just adds complexity.

Execution risk is another real concern. Owning a supply chain means owning the problems that come with it. Labor issues, procurement volatility, software outages—these become internal failures rather than third-party disputes. If a company is not structured to handle those responsibilities, integration can slow growth and introduce new fragility.

Cultural mismatch can also undercut integration efforts. A SaaS company acquiring a logistics partner or a retailer trying to run a tech development team can struggle with misaligned incentives, workflow incompatibility, and leadership conflicts. Integration is not just financial—it requires cultural translation across very different operating domains.

Capital misallocation is a subtler but dangerous trap. Especially for companies with access to cheap capital, the temptation to integrate aggressively can lead to investments that don’t deliver long-term ROI. This was visible in several DTC brands that raised large rounds, built internal fulfillment systems, and later had to scale back or unwind when revenue growth stalled.

Finally, integration can limit strategic optionality. A company that owns too many fixed assets may find it harder to pivot, scale selectively, or respond to shifts in customer behavior. In some markets, flexibility and focus matter more than control.

The lesson? Vertical integration is not inherently good or bad. It is a strategic tool, and like any tool, its value depends on timing, execution, and context. The best operators treat it as a lever to shape their ecosystem—not a checkbox to signal maturity.

Vertical integration is back—but it is not the same game it used to be. Today’s smartest operators and investors use it to build systems that are faster, more defensible, and more aligned with customer needs. They integrate when it sharpens the moat, strengthens the margin profile, or accelerates speed to market. But they also know when to stop. Integration without purpose is just expensive control. Real value comes from using integration to create coherence—across data, operations, and experience. When done right, it doesn’t just make a business more efficient. It makes it harder to compete with.